What is it about an idea that withstands the noise of time? Julian Barnes posits that it is ‘only that music which is inside ourselves – the music of our being – which…over the decades, if it is strong and … Continue reading

What is it about an idea that withstands the noise of time? Julian Barnes posits that it is ‘only that music which is inside ourselves – the music of our being – which…over the decades, if it is strong and … Continue reading

Performances Lights Out Wonderland (2012): Director/Producer/ Playwright The Little Arts Academy Home (2011, 2012): Director/Producer/ Playwright The Little Arts Academy The Prodigies Lab (2011): Director/ Playwright The Little Arts Academy Poems for Andrew (2011): Narrator/Director/ Playwright The Little Arts Academy … Continue reading

Last night we battled our fears together.

We took turns to be each others’ fears

Standing there as my hand was put over my mouth – a silent scream

My other hand was extended

reaching for air,

my legs, crafted to display

straining, pushing forward

but never moving.

Held back by my own hand.

She danced

She stood up to her fears

She danced

She displayed absolute control

She danced

Swiping away all that stood in her way.

She danced.

@LakesideFSC. #reimagineplaces

In response to poems written by 11-year old girls, shared at Listening Voices and Telling Stories by Zanib Rasool, Kate Pahl and Mowbray Gardens Library Group #AHRCutopia

Belief is the only weapon you hold for the future

Angles (not angels) are the imperfect guardians of beauty

You perceive them with experience

You have been trained to differentiate

The lies from the imagined worlds

You alone will realise them

You were born in a world

without stability

So change is a confidant

And instability is the only

constant that you trust.

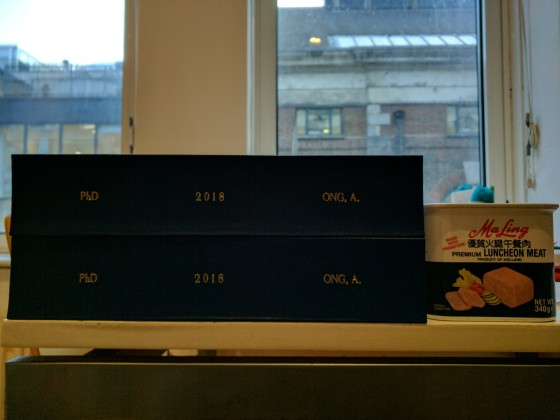

14 August 2018: Confirmation of Award – Doctorate of Philosophy.

3 August 2018: Submitted the final thesis.

9 April 2018: Passed the Viva with minor corrections.

12 January 2018: Submitted the thesis.

Compassionate Mobilities: Towards A Theory For Negotiated Living

Compassionate mobilities works towards a theory for negotiated living inspired by urban practices like parkour, art du déplacement, breakin’ and graffiti. It explores compassionate ways of being together, in a shared place. The need for compassionate mobilities might be seen most clearly in the hypercompetitive pursuit of upward income mobility through education in Singapore. Fear is the main political affect that drives this hypercompetitiveness. A deep sense of loss hinders the imagination of a more hopeful and compassionate narrative of future Singapore. Compassionate mobilities is an emerging theory that proposes how we might live together, in a place shaped by fear and loss, negotiating different hopes for this shared place. Compassionate mobilities works towards tempering these hopes (an imagination of the future that compels interventions in the present) with compassion and proposes an imagination of the future as multispatialities (a term I use to describe a way of imagining the future as multiple places, holding multiple narratives, coexisting in the same location).

Observations of parkour, art du déplacement, breakin’ and graffiti offered some initial ideas towards compassionate mobilities. Over 25 workshops in London and Singapore, these urban art-inspired place practices formed the basis of a theory of compassionate mobilities. These workshops were undertaken with young people between the ages of 15 and 25, mostly in school settings. Part I will focus on establishing the theoretical and contextual basis for compassionate mobilities. Part II will offer some ideas for the negotiation of place using urban art-inspired place practices to initiate compassionate relationships and alternative imaginations of the city that are not constrained by fear and loss.

—-1 February 2015—

A Poem (instead of an abstract): Compassionate Mobilities

This is a ‘conventional’ thesis.

Put your hands on the table.

Rest your cheek on one hand.

Pay attention to texture and temperature.

Where hand meets table

and cheek meets hand.

This is a ‘conventional’ thesis

that asks

how parkour, skateboarding, graffiti and ‘breaking’ (also known as ‘breakdancing’)

might open up

opportunities and possibilities

for young people in Singapore.

These urban placemaking performances

are (I suggest) active metaphors

opening up new narratives

composing alternative pathways

within Singapore’s highly-ordered landscape.

This thesis will focus on young people in Singapore

between 14 and 20 years of age.

Black cold fences with slippery rails.

One step in front of the other.

Social geographer Doreen Massey defines ‘space’,

as ‘a simultaneity of stories-so-far [and]

places are collections of those stories’

(Massey 2005: 130).

Light green leaves on dark brown branches

tickle your face.

Do not be tempted to rely on them for support.

But what can urban placemaking performances do for those who struggle with getting out of bed and accomplishing everyday tasks, you might ask?

Trust your feet.

Individuals immerse themselves in ‘place’

physically, imaginatively, or both.

Crawling backwards

to that time when we were…

‘Place’ is more than what is experienced right now.

Bitter cold

black hands like tarred walkways.

This ‘conventional’ thesis

will playfully

interrogate some old stories,

disrupting/interrupting/retelling,

as it instigates experimental, exploratory

rewriting of stories

by young people for Singapore

through collaboratively facilitated applied performance workshops

with skateboarders, parkour practitioners, graffiti artists, and dancers

in London and Singapore.

In composing activistic placemaking performances

a theory of compassionate mobility emerges,

offering an alternative to ‘social mobility’

which has far to go in terms of imagining

what an inclusive city/society/nation might be.

Bibliography.

‘I am the girl who ran and kept on running, who ran herself to the ground.’ (David Lane, FREE, 2014).

Blood red crevices, striated upon my back.

A dull throbbing bass pulls my legs down, taunting me to escape.

216 more minutes to sunrise.

Tears dissolve the incense dust as prayers take flight at Waterloo.

Sticky palms covered in concrete grey

ash.

no. it is just my sweat finding comfort in the dirt

knowing that it is where I will return one day.

But for now, let me #reimagineplaces.

NOTE:

This poem was written in response to a line from David Lane’s FREE (as seen above), during an amazing workshop with ADD Academy’s Ben Boeglin and Fagan Cheong, Laurent Piemontesi (who was in-residence at ADD Academy SG) and 10 participants from DADP at Singapore Poly.

Photo Credit: Bernie Ng

The research question:

“Attaching Youth to Urban Arts: exploring the significance of attachment between young people and ‘risky’ art?”

This is a journal of sorts, detailing the research findings and thoughts…

Week 1: Taking stock of ‘Know How’ and ‘Know That’ (Nelson 2012)

Pearce highlights that a child is able to form “multiple attachments”, not just with one’s parents but also relatives and alternate caregivers and asserts that in social-emotional development, it is not about the relative significance of singular attachments, but rather, how the network of attachment figures support the individual. Pearce (in explaining Bowlby) is comparatively brief on how secure attachments lead to a “sense of self”, stating only that the child perceives himself to be “good, lovable and competent” when care is “consistent, sensitive and encouraging” (Pearce 2009: 18). Winnicott elaborates in Playing and Reality that “It is in playing and only in playing that the individual child or adult is able to be creative and to use the whole personality, and it is only in being creative that the individual discovers the self” (Winnicott 2005: 73). Winnicott then links the adolescent’s need to test the security of attachment back to this discovery of self, stating that adolescents need to constantly test “security measures” because are:

“meeting frighteningly new and strong feelings in themselves, and they wish to know that the external controls are still there. But at the same time they must prove that they can break through these controls and establish themselves as themselves” (Winnicott 2006: 46).

Week 2 & 3 – Gathering ‘Know That’ (Nelson 2012)

Graffiti in Singapore remains an illegal act of vandalism. Urban artists like Trase and Sticker Lady use their art in ‘risky’ ways that push boundaries in Singapore in order to expand the territory claimed for artistic expression, advocating for freedom of speech in public spaces. Conrad argues that “youths’ risky or resistant behaviour could be seen as infrapolitical performative acts through which they appropriate (tacitly or deliberately) the mainstream portrayal of ‘deficiency’ and ‘deviancy’” (Conrad 2005: 31). Without romanticising the risky and transgressive actions of urban artists, I argue that urban artists have succeeded in expanding the definition of art and creating value for urban arts. OCBC Bank in Singapore recently commissioned Trase to create an artwork for the bank’s headquarters. The artwork intentionally lends itself to multiple (subversive) readings that critique the dominant discourse of capitalism as driver of innovation through competition (see picture above).

Week 4 & 5 – Deciding on our ‘Know What’ (Nelson 2012)

I am enjoying Broderick Chow’s ‘Parkour and the critique of ideology’ where he achieves heightened physical awareness of his surroundings saying, “I became aware, in that moment, of the oppressiveness of the architectural design in this council housing. It is only in using a wall in a paradoxical way that I understood its function…Why is this wall so high? Who is it trying to keep out? Or in?” (Chow 2010: 150 – 151) I decide to borrow Chow’s psychogeography to analyse focus on skateboarding, graffiti and breakdancing. Psychogeography is defined as “the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, whether consciously organised or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals“ (Knabb 2006). Guy Debord and The Situationists popularised the practice of psychogeography in the mid-1950s and sought to challenge the consumption-oriented transport routes and routines by drifting through the city led by one’s pleasure and whim in a ‘derive’. Where one reflects on the psychological effects of the environment so that people become critically conscious of consumerism and “the emptiness of their lives” (Nicholson in Govan et al. 2007: 141). Anderson observes that, youths are “liminal beings” caught between childhood and adulthood and they occupy a “grey area within the mainstream: in terms of their age and the places they can go” (Anderson 2009: 133). Could this liminality be the key to understanding how ‘risky’ behaviour acts as a form of resistance?

Week 6 – 9 – Our ‘Know What’ + ‘Know How’

1. If the “indestructible environment” is not found at home, then youths will look to find secure attachment in the streets, through their art. Without family support, redirection is inevitable. We find evidence of this in our interviews where anger is turned into a productive and creative force.

Tim’s graffiti walk down Bricklane, Lena, Tim and Sasha’s interviews – they unhesitatingly state that their art is an outlet of expression when there is a need to vent anger and aggression.

In an interview with Lena, G says, “Writing it calms me down and I use it as my stress release as I just turn everything into spoken word”. Lena translates this into poetry, saying, “G used the spoken word to vent and his anger was contained, actioned through verbal punches and pattered out words”.

With Tim, E says, “When I’m angry I just sing and I’m trip again, off the air! Sometimes they don’t make sense after”. D, a graffiti artist says “it can be a good way of getting your aggression out’ and Rayner from Urban Legends says, “street dance reflects a certain situation…its part of their culture to dance, and on top of that they are angry and frustrated…dancing becomes a way to let out the frustration. Back in the day people felt a sense of injustice about their lives and street dance was a way to express them”. I know breakdancing saved my friend’s life. He would get into fights over a cheeseburger. He couldn’t express this anger at home and he couldn’t control it either. Then he found breakdancing and the battles gave him an outlet for his aggression. He’s worked out most of his anger now and is much more mellow.

With Tim, E says, “It’s the only thing that can put a smile on my face…If couldn’t have any attachment to music or singing I’d miss everything the feeling when I sing If I sing a song now and someone’s assessing you like and they say it was good or it wasn’t good – It’s good to get compliments it boosts your confidence and it make you feel good it makes you feel that what I actually put effort into people appreciate”

Winnicott and Bowlby concur that aggression can be productive: “angry behaviour between members of a family can often be functional…in the right place, at the right time, and in the right degree, anger can serve to maintain these vitally important long-term relationships” (Bowlby, 1988: 81). This resonates with O, a DJ who acts like a brother to the rap group at Brady Arts Centre. He posts, “I hate it with a passion that I’m more productive when I’m angry”.

2. Not all of them are able to find secure attachment figures. But they do find a sense of ‘self’, and when this sense of self is validated and accepted by the urban arts community, these youths also find “a sense of belonging”. They find their identity through the community identity defined by the urban art practiced. The aliases BBoy Felix, DJ Wonder Woman, Trase are examples of how one’s identity is defined by one’s chosen urban art.

E says: I have a different life. (Laughs) So our main thing in Skinny Latte was to have, not personas but be the people that we wanted to be, that we are not brave enough to be. N, interviewed by Tim says, “Just because you go through the hard stuff doesn’t mean that can’t come out on a good note. I don’t just have to be N from southeast London”.

Tim: Would you say then that you wouldn’t have got that confidence at home?

N: No. Without a doubt no.

Spoken word poet C says, “I wouldn’t say I have a specific mentor, but it is life which I use as my teacher to help me better myself as a poet.” Female skateboarder H says there wasn’t one person, but a community of people who “helped me and inspired me. I can’t remember anything specific but there’s just like everybody helps everybody within skateboarding, and like eggs each other on.”

3. Our interviews also indicated repeated mention of the urban arts community as “family”. Wansmoof, the street dancer I interviewed from Singapore said, “You always hear the phrase, “We are not a crew. We are family…” The name of a crew is like a family name to us…I will stand by my crew, if anyone starts dissing my crew…Same goes to anyone tries to cause problems to my real family or family name”.

Music producer K says, “The people I work with musically are family, they could only be family, how could I work with those I’m not close to?” “A rhetorical question”, Lena reflects, “that may not always be one satirically posed by a big time music producer; yet from a Nigerian young man who found himself in Marsh Farm, Luton, one of the most deprived wards; trust doesn’t always come too easily for him.”

Interestingly, Pure Evil who just completed a ‘tour’ in South Africa painted a picture of his newborn son, Bunny, on a wall of a house with the permission of its owner who recognised the commercial value a nice work of graffiti would bring to his property. By organising a trip to paint in Woodstock, South Africa, was Pure Evil reliving Woodstock of the 1969? Why did Pure Evil feel the need to paint a picture of his son – a performance home when away from home?

4. Wanting to “heal” others through their art

Neumark observes that, “Artistic practice, often through its inherent repetitive nature, invites the possibility for validation and integration” (Neumark in Kuppers & Robertson 2007: 147). Participants find “healing” as they use the symbolic language of art to “risk” revealing one’s memories and self to others. Neumark argues that “creativity, violence and the tendency to want to save others are intricately linked” (Ibid: 147). We believe this is something applied theatre practitioners should be conscious of in working with urban artists to create programmes.

K, a music producer says, the inspiration for his song ‘Lost Orphan’ was the “reality of our community where kids are being raised by negative role models and nothing but negative deeds are therefore implanted in their thoughts.” K attributes this to “the lack of fathers in our community”. He said, ‘A woman couldn’t fully BRING UP a man’ therefore the loss of a man in a boy’s life plays a big loss in his development. Notice how I said a woman cannot ‘bring up’ rather than ‘raised’”. Lena reports that K says his family “did not respect their art form” and this was commonly expressed by many of the spoken word poets she interviewed.

W, a youth music producer says that he lost his father at a young age. Watching him work with the young people at a youth organisation, Tim reflects that the lack of a father figure may have compelled W to take on the identity of a surrogate father figure to at risk youths that he works with.

However, it is precisely this role that people like W play that inspires young people to want to be a role model for others. One of W’s youths, N, who is interviewed by Tim says, “So for example with me…My brother passed away a couple of years so that was a really big blow and downfall of my life. So with people that have lost family members I want to make them know that, yeah it’s hard at the beginning but you can get through it at the end of it and you can do stuff to dedicate them. Singing brought out my confidence and…So I’d say If I stopped singing I’d go back to the N that wouldn’t talk to anyone.”

The desire to help others through art is communicated through several other interviewees. Spoken word poet C says, Spoken word for me is not something which I use to benefit me, but instead I use it as a medium to be the voice of individuals who have been hurt, misunderstood, underestimated, frowned upon and belittled. It is my way of making people more aware of what others go through.”

E, in her interview with Tim says that music offered, “a way to speak because sometimes speaking isn’t enough…you can say words but to sing it you have to show emotion.”

As I sorted through the findings, I became increasingly frustrated with ethnography’s limitations as a methodology. The mass of findings accumulated was overwhelming, filled with “thick descriptions” but lacking insight or critique of the observed phenomenon.

I turn to psychogeography and that leads me to…

5. Accessibility (affordability) was another aspect of urban arts valued by its practitioners who felt that anyone, any age could participate in urban arts. Many talk of not being able to afford classes and learning from the community who gathered around informal locations like Trocadero for street dance, “Brixton Beach” for skateboarding. It’s about having “accessible expression”, says J2 in an interview with Sasha. “You don’t have to play a certain type of instrument or have a certain type of tool, it is just you and a piece of paper and a pen”.

This jars with the increasing gentrification of areas that have become “hip” because of the urban artists. A mapping of graffiti by Roa, graffiti sighted on the Unseen Tour by the Sock Mob and Tim’s Graffiti Tour of Bricklane centres around Shoreditch High Street overground station and is bordered by City Road, Hoxton Square, Hanbury Street and Spitalfields market. We see the consumption of “a city’s aesthetics and culture” (McRae 2008: 33) through ‘gentrification’ – where it is possible to acquire a “hip” identity through the artists associated with one’s postal code.

The most recent illustration of the cultural consumption that threatens urban arts: Banksy’s Slave Labour which was cut out of a wall in Haringey. It appeared on an American online art auction site. Two enraged “millionaire property developers” accused the Haringey Council of “doing nothing” to protect the work (Wright 2013). Which begs the question, “What moral high ground in community art interests could these property developers possibly claim to possess?” Interestingly, Henry, my Sock Mob guide, tells me that a graffiti artist would never paint over another person’s work unless he has a bone to pick with that person. There is a respect of each other’s work (and place) that comes with the reclaiming of space. Perhaps one loses some sense of respect for others when one is driven by consumption.

I am reminded of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl,

“I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night,

who poverty and tatters and hollow-eyed and high sat up smoking in the supernatural darkness of cold-water flats floating across the tops of cities contemplating jazz…

the madman bum and angel beat in Time,

unknown, yet putting down here what might be left to say in time come after death,

and rose incarnate in the ghostly clothes of jazz in the goldhorn shadow of the band

and blew the suffering of America’s naked mind for love into an eli eli lamma lamma sabacthani saxophone cry

that shivered the cities down to the last radio,

with the absolute heart of the poem butchered out of their own bodies good to eat a thousand years.”

Stranger, in his painting “Needs and Benefits” notes that “Most of the technology we see today is not something we really need…The process of this painting made me think about how the city has been evolving to make it a beneficial place but might end up turning itself into a ludicrous with redundant needs”.

6. Anderson notes that, “Every generation of youth culture, in every place, produces its own groups…youths have constructed for themselves their own identity positions and senses of place” (Anderson 2009: 136). Do youths reclaim a sense of place when they claim an identity position within urban arts? In a case study on territoriality, Kintrea et al. argue that, “territoriality is a kind of ‘super place attachment’…where young people identify themselves topographically. Perhaps urban arts decreases territoriality by providing an alternate identity that becomes more important to the youth than his/her geographical location.

Week 10 – Identifying ‘Praxis’ (Nelson 2012)

In analysing the “significance” of attachment between young people and ‘risky’ art, we chose to focus on “significance” of our findings in regards to four main stakeholders:

i. Youth:

Giroux opines, “Already disenfranchised by virtue of their age, young people…find themselves living in a society that seeks to silence them as it makes them invisible” (Giroux 2012). With the regularity of recessions and collapse of economic institutions, young people no longer enjoy the secure economic futures with stable jobs that their parents enjoyed. They are told to manage their expectations in terms of remuneration and job security whilst being blamed for their ‘unemployability’, viewed as “unproductive, excess and utterly expendable” (Ibid).

Through the urban arts, many of the young artists we interviewed have successfully created a career for themselves. BBoy Felix owns a dance studio that runs street dance classes for professionals. It broke even through the international breakdancing competitions that Felix organises and Felix has renewed his lease for two more years. He currently employs 16 street dancers as teachers and certainly has helped to develop the street dance industry in Singapore.

ii. Family

Despite its numerous positive outcomes, the various forms of urban arts researched (in and of themselves) do not provide an adequate “indestructible environment”. With all reclaimed sites, they are temporal and can be taken away. The effort to save Southbank Undercroft is a case in point. After becoming a “legendary destination” amongst the international skateboarding community, it is threatened again by Southbank Centre with relocation. One skateboarder on the “Save Southbank Skate Park” Facebook Page writes, “We don’t want another purpose built man made skate park, we want to cruise through the streets, finding weird and strange things along the way, using that architecture in ways no one else would have thought of…we want this freedom and this reality, this idea of pure street skateboarding.”

Adolescents need both the secure attachment of a family and the freedom to “break controls” in order to discover their “sense of self” (Winnicott 2006: 46).

What is significant here is that the modern “nuclear family unit”, defined by the Family Policy Social Centre (FPSC) as “a set of parents and their children” (FPSC 2009) does not seem to provide the adolescent with a sense of identity. The identity is created by breaking “external controls of all kinds” as a secure adolescent has confidence in self-control and when “self control is a fact then security that is imposed is an insult” (Winnicott 2006: 46). This is certainly different from the Renaissance family where one’s family name was synonymous with one’s identity, reflecting one’s profession and position in society. The interaction between ‘self’ and ‘society’ produced the ‘identity’ which was then supposed to “stitch the subject into…the fabric of society” (Hall 1992: 276). This is no longer the case today.

I argue that the gaze of urban art communities and their audiences are in fact Lacan’s “formation of the self in the ‘look’ of the Other” (Ibid: 287). Youths find identity in urban arts then “not so much from the fullness of identity which is already inside us as individuals, but from a lack of wholeness which is ‘filled’ from outside us, by the ways we imagine ourselves to be seen by others” (Ibid: 287). Knowing that youth identity is created through the mirror of others in a Lacanian sense when they perform their art for others, the applied theatre practitioner must question the effects of such a gaze and raise consciousness of its possible negative consequences.

Hall argues that the “host of estranged figures in twentieth century literature and social criticism” reinforce the construct of ‘self’ as the “isolated, exiled or estranged individual framed against the background of the anonymous and impersonal crowd or metropolis“ (Hall 1992: 285). ‘Stranger’ as a graffiti alias seems to embody this identity “estrangement”. Does Stranger reclaim a sense of self when he inscribes his alias on a (non-designated) wall? Can the act of reclaiming a space also create a sense of identity “wholeness”?

iii. Society

Following from the above, I argue that it is vital that the funders and policy makers recognise that neglect of urban art development would deprive our youths of a significant positive environment for the shaping of their identity. As Giroux cautions, the demonisation and disposability of youth is tantamount to “suicide” for any society because it encourages a “culture of cruelty in which the ultimate form of entertainment has become the pain and suffering of others, especially those considered throwaways, other, or without consumer privileges and rights” (Giroux 2012).

For property owners, it is also necessary to acknowledge that it is the nature of urban arts to reclaim ‘found spaces’ within the city for its activities. Where a symbiotic relationship has been established between the urban artists and the local community, I argue that property owners should embrace and support this as they would other forms of community art. Obviously the property developers in Haringey appreciate that having a Banksy on its walls increases the property value to their benefit. But the skateboarders at Southbank are not credited with turning the Southbank Undercroft into a world-famous destination for tourists and skateboarders. Spoken word poets perform within Southbank and the Barbican, but some urban art expressions are more artistically validated than others.

Can One Buy Identity?

One worrying emerging trend is the commodification of identities. Giroux says, “kids learn early that social exclusion is tied to one’s status as a shopper, that identities are determined by owning the most fashionable commodities” (Giroux 2010: 55). There is an ongoing ‘war’ between skateboarders and hipsters who pose as skateboarders. Owning a longboard, or a penny skateboard, has become the new indicator of ‘hip’. In his mockumentary Exit through the Gift Shop, Banksy satirises the art world’s fascination with acquiring graffiti, as if exhibiting a piece of wall in their homes buys ‘street cred’. As much as urban artists fight against it, can they resist being assimilated into consumerism?

iv. To the field of applied theatre:

There is a growing body of research, particularly in the fields of cultural and social geography, that explore attachment theory in relation to youths’ engagement in urban arts. As an applied theatre researcher and practitioner, I am compelled to question the intention of competitions and reality contests that commercialise the visually spectacular nature of urban arts. Commercialisation pigeonholes youths into categories established by corporations who seek to turn youths into products fit for consumption. Giroux highlights how this unbridled consumerism that over-sexualises young girls and militarises young boys produces “future generations of young people who cannot separate their identities, values, and dreams from the world of commerce, brands and commodities” (Giroux 2010: 32). Can applied theatre practitioners afford to stand by whilst the identities of our youths are commoditised?

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, J. (2009) Understanding Cultural Geography: Places and Traces, Oxon, Routledge

– Youths as “liminal beings” experimenting with their youth cultures on the margins

– how this threatens the mainstream

– tribalism or tribal behaviour in youth culture

Barrett, E. and Bolt, B. (eds.) (2007) Practice as Research : Approaches to Creative Arts Enquiry, London, I. B. Tauris.

– not particularly persuaded by PaR. I am still skeptical of how some people might try to pass off producing an interesting collaborative performance or artwork as a piece of “research”

Bentley, T. and Gurumurthy, R. (1999) Destination Unknown: Engaging with the Problems of Marginalised Youth, London, Demos.

– there is a useful chapter here on youths and their relationships with adults

Bowlby, J. (1969) Attachment And Loss: Volume I, Attachment, London, Hogarth Press.

– useful chapter on nature and function of attachment behaviour

Brock, J. (2013) ‘Campaign aims to bring Banksy home’, HARINGEY TODAY, http://www.haringey-today.co.uk/News.cfm?id=6493 (accessed 7.3.13).

Chow, B. (2010) ‘Parkour and the critique of ideology: Turn-vaulting the fortresses of the city’, Journal of Dance & Somatic Practices, Vol. 2, No. 2: 143 – 154

– psychogeographic analysis of parkour

– notions of alienation and territoriality explored

Clayden, J. & Stein, M (2005) Mentoring Young People Leaving Care: ‘Someone for Me’, York, Joseph Rowntree Foundation

– I like how this explores the long-term impact of having a mentor on young people leaving care

– very detailed interviews with mentor and young people on how they were matched, how often they met, what the mentor helped with specifically and post-mentoring reflections.

– young people were able to express preferences for mentor. e.g. a young women wanted a mentor who was also a young mother so she would be able to empathise and support with knowledge.

– mentoring could involve practical knowledge like how to shop for groceries, decorating their house, managing their finances, getting around via public transport etc. these are things we take forgranted, but they are not easy for young people leaving care.

Conrad, D. (2005) ‘Rethinking ‘at-risk’ in drama education: beyond prescribed roles’,Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, Vol. 10, No. 1: 27 — 41

– On redefining ‘at risk’ youths and how risky behaviour is a form of resistance

Cross, L. ‘Banksy Haringey mural auction ‘will stop if protesters prove theft’ | Metro News’, Metro, 1923, metro.co.uk/2013/02/23/banksy-responds-as-missing-haringey-mural-set-for-auction-3510607/ (accessed 7.3.13).

—– ‘‘Missing’ Haringey Banksy pulled from Miami auction at 11th hour’, Metro, 1924, metro.co.uk/2013/02/24/missing-haringey-banksy-pulled-from-miami-auction-at-11th-hour-3511335/ (accessed 7.3.13).

– link to Sock Mob tour where Henry was telling us that Banksy got so frustrated with people cutting out his work and selling it off that he decided to cut out his own artwork, make a copy of it on the wall and sell off the original so he could survive. Banksy now has his own gallery and people say that he has sold out. But an artist has to survive…and how else would one do that in this age of capitalism?

Debord, G. (2009) Society of the Spectacle, Eastbourne, Soul Bay Press.

– the guy who really developed the idea of Psychogeography.

– most of his work is now online as well at http://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/index.htm

De Certeau, M. (1984) The Practice of Everyday Life, (trans. S. Rendall) Berkeley, University of California.

– the person who first came up with the idea of the flaneur, someone who is guided to walk the streets by pleasure…where his movements are not dictated by work or shopping

Denzin, N. (2003) Performance Ethnography: Critical Pedagogy and the Performance of Culture, London, Sage

– A passionate call for ethnographers to engage in “performance sensitive ways of knowing” and for more “dialogic” fieldwork

Dickens, L. (2008) ‘“Finders Keepers”: Performing the Street, the Gallery and the Spaces In-between’, Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1: 1-30

– A riveting analysis of grime chic and the tensions/pressures placed by the art world on the graffiti world

Dickens, Luke(2010) ‘Pictures on walls? Producing, pricing and collecting the street art screen print’, City, Vol. 14, No. 1: 63 — 81

– An analysis of Banksy’s Paintings on the Wall production house that manufactures screen prints of his street art

Duncombe, S. (2002) Cultural Resistance Reader, London, Verso.

– I really enjoyed the Manifesto for Walking article by Wrights & Sites because it showed how walking can be guided by pleasure (as a flaneur would) instead of being guided by work or consumption

– I also enjoyed the flash mob party on the train

Gallagher, K. (2008), The Methodological Dilemma: Creative, critical and collaborative approaches to qualitative research, Oxon, Routledge

– Loved Ch 5 on Performed Ethnography

– this provides a good defense of performance ethnography, and its strengths and weaknesses. We should highlight some of the issues surfaced here during our Performing Research presentation where it is necessary to illustrate that we are aware of the limitations in our research and did xxx to mitigate it

Gallagher, K. and Fine, M. (2007) The Theatre of Urban: Youth and Schooling in Dangerous Times, Toronto, Buffalo, University of Toronto Press.

– this is an example of THICK DESCRIPTION which Nicky advised us to do for our ethnographic methodology

Govan, E., Nicholson, H. and Normington, K. (eds.) (2007) Making a Performance : Devising Histories and Contemporary Practices, Abingdon, Routledge.

– I loved “Between Routes and Roots: Performance, Place and Diaspora” in ‘Performance Place and Diaspora” where Helen Nicholson talks about how “contemporary perceptions of indentity are formed by identifying with, and travelling between, different locations and multiple places.” (p136). She says, “spatial practices are therefore often reconfigured and unfixed in performane and how place is conceived, lived and perceived becomes redefined.

Giroux, H. (2010) Youth in a Suspect Society: Democracy or Disposability?, New York, Palgrave Macmillan

– a good argument here about how consumer culture has shaped the desires and aspirations of our youths. how youths today only think about their future in terms of having the power to be a ‘good consumer’ or being famous (celebrity) and becoming “a brand”. talks about how we have contributed to this sorry state of affairs. sobering.

Giroux, H. (2012) ‘”The Suicidal State” and the “War on Youth”‘, truthout, truth-out.org/opinion/item/8421-the-suicidal-state-and-the-war-on-youth, 10.04.12 (accessed on 04.04.13)

Hall, S., Held, D. and McGrew, T. (1992) Modernity and its Future, Cambridge, Polity Press and Open University

– On postmodern identity

Harvie, J. (2009) Theatre & the City, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

– talks about cultural materialism and performative analysis

– also mentions Guy Debord’s derive and psychogeography and the De Certeau flaneur

Hopkins, D.J., Orr, S. and Solga, K. (eds.) (2009) Performance and the City, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

– I enjoyed reading about the work of artists after 9/11. Recreating healing memories through performances in the city

Kintrea, K, Bannister, J. Pickering, J, Reid, M & Suzuki, N. (2008) Young People and territoriality in British Cities, UK, Joseph Rowntree Foundation

– breaks down reasons for territoriality in gangs and how this leads to violence

– uses case study of 6 areas to analyse with interviews of people in gangs and in the areas

– I found this really relevant to our group research….whilst gangs certainly express a high amount of territoriality, the ‘tribes’ formed by youths through urban arts may not (Canan mentioned their attachment to ‘place’ is ephemeral).

– it made me curious….and i don’t know about London, but in Singapore, the youths in general know that they are trespassing, that they are using a non-designated space. so when they have to leave, they just treat it as part of the nature of the relationship they have with the space. Perhaps one of the aspects of Urban Arts is this ability to de-escalate territoriality?

Knabb, K. ‘Situationist International Anthology’, Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006,http://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/index.htm (accessed 7.3.13).

Koh, J. (2012) ‘Sticker Lady’s Arrest: Is there space for street art in Singapore?’, Facebook page, Janice Koh, www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=414236755288024, 05.06.12 (accessed 19.01.13)

Kuppers, P. & Robertson, G. (eds.) (2007) The Community Performance Reader, London, Routledge

– Conquergood on the ethical dilemmas of performance ethnography: four sins of the ethnographer + advocacy of dialogic practice.

– Neumark on the healing nature of creative practice that uses symbolic language to mitigate the risk of revealing intimate details of ourselves through our memories

Lee, A. (2013) ”Sticker lady’ Samantha Lo pleads guilty’, TODAY,www.todayonline.com/singapore/sticker-lady-samantha-lo-pleads-guilty, 02.04.13 (accessed on 22.04.13)

Lefebvre, H., Kofman, E. (ed.) and Lebas, E. (ed.) (1996) Writings on Cities, Oxford, Blackwell Publishing.

– Three representations of space and how this is controlled.

Lo, S. (2011) ‘An Interview with Urban Artist Trase One’, The CANVAS,www.thecanvas.sg/showcase/interviews/an-interview-with-urban-artist-trase-one/, 15.02.11 (accessed on 20.01.13)

Lyall, S. ‘Borough Searches for Taken Banksy Mural – NYTimes.com’, 1928,http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/01/world/europe/give-us-our-banksy-mural-back-londoners-say.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0 (accessed 7.3.13).

Mackey, S. & Whybrow, N. (2007) ‘Taking Place: Some Reflections on Performance and Community’, Research in Drama Education, Vol. 12, February 2007, No. 1: 1-14

– helpful to contextualise the space/place debate

McRae, J. (2008) Play, City, Life: Henri Lefebvre, Urban Exploration and Re-Imagined Possibilities for Urban Life, Unpublished PhD Thesis, Kingston, Ontario, Canada, Queen’s University

– Gentrification, consumption of city space. Buying the city. Buying an image?

Nelson, R. (2012) Evidencing the Research Inquiry, Lecture, CSSD, 15.01.13

– Useful for understanding the different phases of research and classifying different modes of knowing through findings collected.

O’Brian, A. & Donelan, K (eds.) (2008) The Arts and Youth at Risk: Global and Local Challenges, Cambridge, Cambridge Scholars Publishing

– Very crucial in highlighting the problems of defining youths as ‘at risk’ and evaluating various interventions undertaken with such youths. In particular Cahill worries me as she cites evidence that “at risk” youths who have undergone “helping programmes” may suffer more long-term negative effects in comparison to youths who did not undergo any programme at all

O’Toole, J. & Beckett, D. (2010) Educational Research: Creative Thinking & Doing, South Melbourne, Victoria, Oxford University Press.

– very useful in describing different methodologies possible

Pearce, C. (2009) A Short Introduction to Attachment and Attachment Disorder, London, Jessica Kingsley.

– A good examination of Bowlby’s attachment theory and how this relates to observed attachment disorders

Prentki, T. & Preston, S. (2009) The Applied Theatre Reader. London, Routledge

– Bell hooks on the margins. Need a community for resistance

Seah, M. (2013) ‘Movin to the Groove’, TODAY,www.recognizestudios.com/downloads/BreakinBad/BreakinBad_2.pdf, 16.01.13 (accessed on 03.04.13)

– breakdancers are not delinquent youths

Skelton, T. and Valentine, G. (eds.) (1998) Cool Places : Geographies of Youth Cultures, London, Routledge.

Storey, J. (ed.) (1994) Cultural Theory and Popular Culture: A Reader, Hemel Hempstead, Harvester.

Taylor, S. (2009) Narratives of Identity and Place, London, Routledge.

Wertz, F.J.J. (2011) Five ways of doing qualitative analysis: phenomenological psychology, grounded theory, discourse analysis, narrative research, and intuitive inquiry. New York; London: Guilford.

– Useful for grounded theory and phenomenological methodology

Whybrow, N. (ed.) (2010) Performance and the Contemporary City: an Interdisciplinary Reader. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

Winnicott, D.W. (2005) Playing and Reality, Oxon, Routledge Classics.

– one can only discover one’s self through play

Winnicott, D.W. (2006) The Family And Individual Development, Oxon, Routledge Classics.

– I found the need for adolescents to test security in the family environment very relevant and it chimes with Tim’s findings on “indestructible environment”

Wisker, G. (2008) The Postgraduate Research Handbook, Hampshire, Palgrave Macmillan

– a really easy to understand, break it down in simple english guide on methodology, grounded theory, action research, data analysis strategies and lots of useful tips about managing your supervisor 🙂

Wright, H. ‘Council did ‘nothing’ to protect Banksy (From Haringey Independent)’, 1926,http://www.haringeyindependent.co.uk/news/10252342.Council_did__nothing__to_protect_Banksy/(accessed 7.3.13).

Calling all young women!

Get strong, get fit and have fun! In this parkour x theatre workshop you’ll learn pick-up some basic parkour moves that will be combined with theatre improvisations.

Note: we’ll be joining Parkour Generations for a Beginners’ Outdoor class for the first part of the lesson and this lesson moves around a lot so please do not be late as we will not be able to go back to the meeting point to get you.

This workshop is part of a three-year research project that will involve collaborations with skateboarders, b-girls and street artists. The minimum age required for participation is 14 years of age.

Date: 27 Sept 2014

Time: 10.15am – 1pm

Meeting point: Kilburn Park Tube Station exit

Please email me at adelina.ong@cssd.ac.uk / onelab2010@gmail.com if you’d like to attend.

Abstract